As business and government leaders struggle to protect public health and forestall economic devastation in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic that has already sickened 351,731 people and killed 15,374 world-wide, scientists are racing to understand how the novel coronavirus works.

The disease Covid-19 is caused by the virus SARS-Co-V-2. It’s one of several corona viruses that have caused diseases such as the common cold, flus, SARS, and MERS, in humans. These viruses can enter the body through the mouth nose and eyes, and health experts warn the members of the public to wash hands regularly and keep hands away from the face. Covid-19 seems to be more dangerous than flu or SARS. There is no medical treatment or vaccine.

Can’t smell or taste? You may be infected.

Early symptoms can mimic colds and flu. A New York Times story by Roni Caryn Rabin reports 30 percent of 2,000 South Korean patients who tested positive for the virus lost their sense of taste and smell. Doctors in several other countries have found a loss of both senses in Covid-19 patients, and consider those losses a likely infection marker. British ear, nose and throat doctors say people who suddenly lose ability to smell and taste, even if they have no other symptoms, should suspect they’ve been infected and self-isolate for seven days.

We’ve been told that the illness is spread by droplets in the air caused by coughing, sneezing and breath of infected persons and by contact with infected surfaces. A New England Journal of Medicine report on the life-span of the virus molecules outside a human host’s body says they can remain viable in air for up to three hours, on plastic and steel for up to 72 hours, on cardboard for 24 hours, and on copper for four hours. Under certain conditions these pathogens may live longer.

The New York Times has a graphic of How Coronavirus Hijacks Your Cells

How the contagion works

|

We’ve all seen of the illustrations that show a SARS-Co-V-2 particle as a ball tightly covered with ominous looking club-shaped red spikes. A Nature story by Smriti Mallapaty explains the significance of those spikes, and the reasons Covid-19 seems to be more contagious than seasonal flus and the virus that caused SARS.

According to the Nature story, genomic analysis has shown that the SARS-Co-V-2 virus has a spike protein that it uses to infect target cells, a process in which its protein binds to the membrane of the target cell. The binding maybe activated by specific enzymes. Unlike its close relatives, the story says, the SARS-Co-V-2 virus appears to have a protein that is activated by the host cell enzyme furin. Because furin is found in many human tissues, including those of the lungs, liver and small intestines, the virus has potential to attack multiple organs. Chinese researchers found that other related coronaviruses don’t have furin activation sites.

A team of researchers at the University of Texas at Austin found that a Sars-Co-V-2 protein binds very tightly to receptor in human cells—called ACE 2 receptors. The identification of receptor sites, the story says, suggest the possibility of future vaccines or therapies that could block receptors and make it harder for the invading protein to enter the cell. Read the story here. Researchers say more study is needed on activation sites.

An ancient protector: Soap

Soap maybe the best defense against infection. Recipes for soap made from fat, wood ash and water have been found on Babylonian clay containers dating back to 2800 BCE. And this ancient invention and its descendants efficiently attacks today’s scourge. Palli Thordarson, a chemistry professor at the University of New South Wales, who posted a viral Twitter thread on the wonders of soap, explains how soap doesn’t just wash the viral molecules away. It demolishes them.

Thordarson explains soap is made of molecules called amphiphiles that have a dual nature. One end of the molecule is attracted to water and repelled by fats and proteins. The other side of the molecule is attracted to fats and is repelled by water. It’s this dual-nature chemical construction that makes soap so effective. “When you buy a conventional soap, it consists of a mixture of these amphiphiles,” Thordarson explains. “And they all do the same thing. ”

The SARS-Co-V-2 virus is an enveloped virus, which means basically that it lives inside a protective layer of fat. The fat-loving side of the soap molecules burrow into the virus’s fat layer and tear it up, while the soap’s water-loving side pulls it into the wash water, wrecking the whole structure. The viral structure has to be intact to infect a cell. Thordarson says regular soaps are fine. Agents that fight bacteria won’t fight viruses, and Thordarson doesn’t recommend antibacterial soaps anyway.

Watch soap smashing the viral particles: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s2EVlqql_f8&feature=emb_share&fbclid=IwAR0QVpN1JVfzLmyMCUEghxfu30jiySTMn9P7amT96k8DWKlLFaE7zyfWanc

Now What?

Right now, SARS-Co-V-2, and its cascading impact, leaves us with more question than answers.

How do complex systems—such as economies and the public health—respond when perturbed by massive events such as natural disasters and the spread of a deadly disease?

What happens to large systems in the aftermath of extreme perturbation? Will they ever be the same again? What conditions would let them bounce back to something like their previous state? Or should they?

South Korea used GPS tracking to find patients who violated quarantines, and offenders were fined. In China, officials went door to door and took temperatures, ordering those with fevers not to leave home. These extreme measures apparently halted the spread of infection. Will Western societies tolerate such intrusions?

What can we expect to learn from the pandemic of 2020?

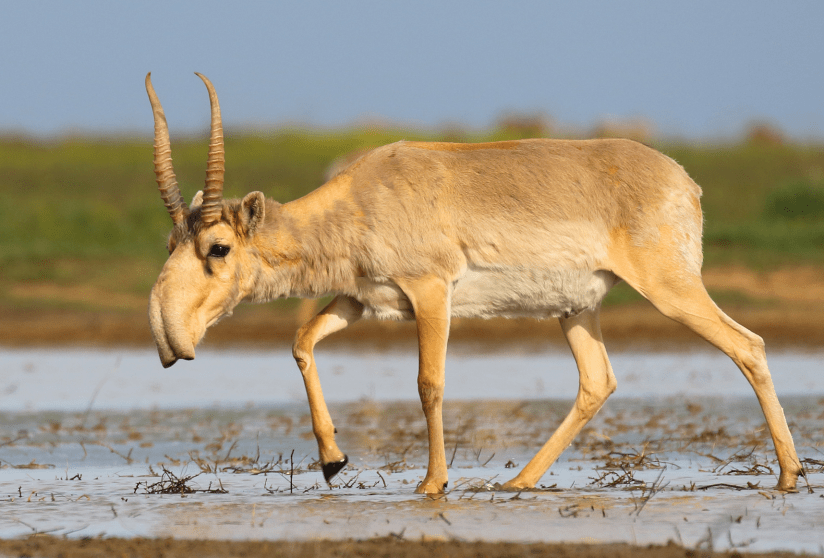

Will climate change and human destruction of natural environments create conditions that favor more novel diseases and more pandemics?

An MME can push a species closer to extinction. But human health and fragile animal food webs are also at risk. Tidal pools on the west coast, for example, were once hosts to a healthy mix of species, including mussels and sea urchins. Starfish are voracious predators, that gobble mussels, sea urchins and other creatures. With starfish diminished, numbers of muscles and sea urchins are increasing, causing decline in availability of kelp. Kelp is a major source of food for sea urchins and many marine invertebrates. Scientific studies have shown

An MME can push a species closer to extinction. But human health and fragile animal food webs are also at risk. Tidal pools on the west coast, for example, were once hosts to a healthy mix of species, including mussels and sea urchins. Starfish are voracious predators, that gobble mussels, sea urchins and other creatures. With starfish diminished, numbers of muscles and sea urchins are increasing, causing decline in availability of kelp. Kelp is a major source of food for sea urchins and many marine invertebrates. Scientific studies have shown